My journey as a Djangonaut - from zero to contributor in one space mission

Disclaimer: I’m a fan of open source. The spirit of openness and collaboration just makes software better, and hackers happier. The benefits of open source are noticeable even if you’re just a user - but multiply when you become a contributor as well.

However, contributing into an existing project is always daunting. Specially when it comes to popular projects, with a huge codebase and thousands of participants - such as the Django project, for example. It’s hard to know where to start, how to proceed, and how to get your changes accepted. For all the years I’ve been working as a software engineer, contributing to open source is something that has always been on my wishlist, but never got to achieve.

But as it turns out, Django has an amazing community and runs a periodic program to help aspiring contributors along their journey into their first contribution to the project: the Djangonauts program. I joined session 5, running October-November 2025.

Similarity to the Coconauts name purely coincidental 😬

Ready for takeoff

The program is whimsically themed around a space mission, so I’m following the same convention through this post. Djangonauts (which are the participants who want to become contributors) are placed into teams leaded by a Captain and a Navigator (which are respectively, experienced members of the community and stablished contributors, whose role is to guide the Djangonauts along their journey). Each team is focused around a Django subproject: there are teams for the Django framework itself, but also for the debug toolbar, Django Girls or in my case, my team was working on Django CMS.

The spirit of the program is that of low-structured guidance and support from senior members of the community to aspiring ones, and between the Djangonaut peers themselves. During the program, each Djangonaut is expected to achieve a contribution into their assigned projects, even if it’s a small one - as more important than the contribution itself, is the experience of the contribution process and the integration into the community.

Start the engines

The first week of the program is used to familiarise ourselves with the project - Django CMS is not as popular as it’s big brother, and none of the Djangonauts in the team were acquainted with it. So the first thing to do was spending some time going through tutorials, documentation and setting up a sample project before we do any hacking.

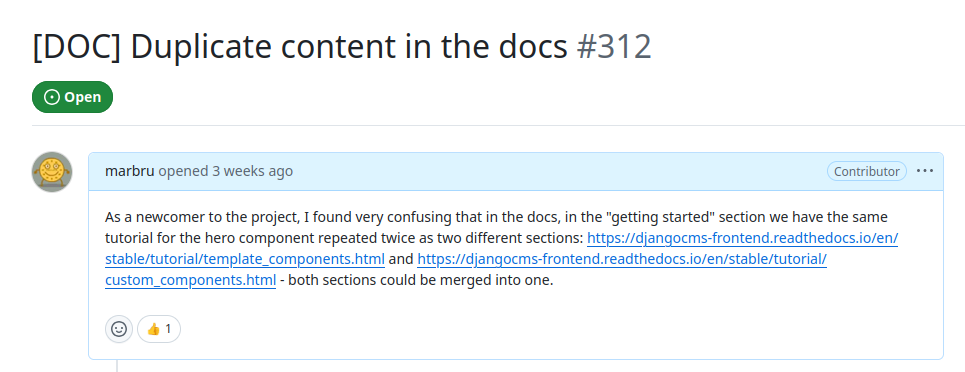

Going through a project onboarding with a contributor mindset is extremely valuable: it’s only the first time that you go through the introductory materials that you get to experience them with fresh eyes, and are able to evaluate it’s effectiveness. So simply going through this learning process, before writing any code, allowed to identify some areas where the documentation was confusing. And as new contributors, we’re encouraged to fix it!

The process of making a change to an Open Source process, even it it’s in the docs, goes through discussion and collaboration with the existing project maintainers. They need to evaluate your change and guide the direction to be taken. So the first step is to raise tickets for the issues that you encountered. Those tickets (or issues, as Github calls them) might give way into pull requests implementing the proposed changes - which might not necessarily be implemented by the same person! Publishing a ticket/issue helps current and future contributors become aware of a bug, a possible enhancement, or even feature ideas, and is in essence another useful way of contributing to open source, without writing any code.

For example, later during the program, we discovered a bug in Django CMS. I raised a ticket reporting it, and our navigator promptly pushed a fix.

Launch!

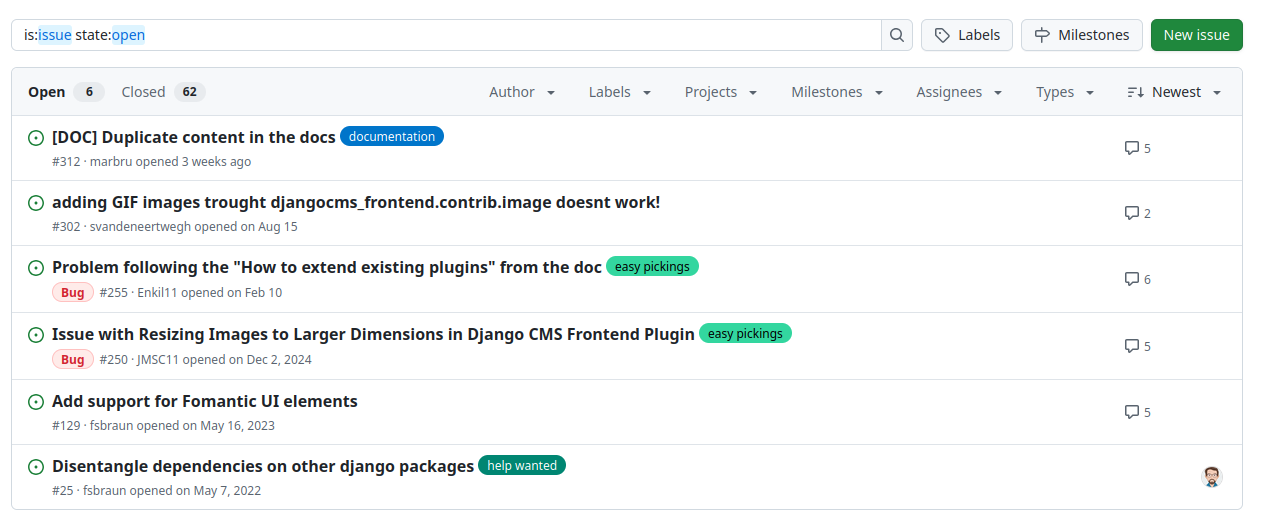

And now comes the time to really get started: our navigator offered a curated list of tickets that are approachable for newcomers into the project, and we are to pick one and start hacking.

This is perhaps the biggest barrier of entry for aspiring contributors in most OS projects - when you are lacking the project context, most tickets won’t even make any sense to you. And here’s where community and curation come to the rescue: many projects use tags for their issues, which can be used for example to tell apart features, from bugs, from documentation. Or a common pattern is to use them to mark tickets that are friendlier to new contributors, with names such as “easy pickings” or “good first issue”.

In my case, I went for a bug ticket, which was marked as “easy pickings”. The ticket had a very clear description on how to reproduce the bug, with even screenshots included - so I settled into doing just that.

And sure enough, reproducing the bug locally was pretty straightforward. But then discovering the source of the bug was a different matter… It turned out to be a tricky one, rather than an easy picking! It required plenty of discussion with our navigator to be able to triage the bug, and decide on a solution - which does not fix the source of the bug, but at least is an UI improvement.

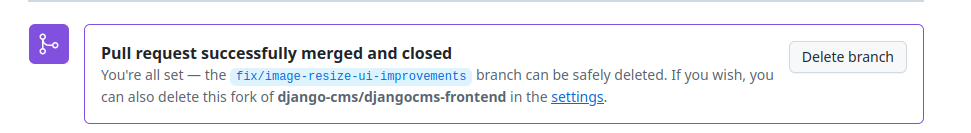

These changes were implemented and raised as a feature pull request. The pull request had a bit of back and forth to get the automated CI system to give it the green light, as well as a passing review from our navigator, which helped make sure the changes were backwards compatible and wouldn’t break existing instances of djangocms. Moving fast and breaking things is not the way of open source!

Success!

Once again, the key takeout is that collaboration with a project maintainer was essential during the process.

Work as a crew

The Djangonauts is not a solo mission: the spirit of the program is collaboration not only with your mentors, but also with the other Djangonauts. There’s a lot of diversity in the participants: not just in terms of geography of demographics, but also there’s people from very disparate backgrounds. There’s people who are already active members of the Python/django community, as well as people with very little exposure to the project, and there’s experienced developers alongside people who are newer to programming. Just like in open source projects in the wild, if you think about it!

The magic of open source is that every part of the process is open, and anyone can collaborate. So even if a ticket is mainly driven by one contributor, it doesn’t mean that others can’t lend a hand as well. As the famous quote goes: given enough eyeballs, all bugs are shallow - i.e., more people have a broader view.

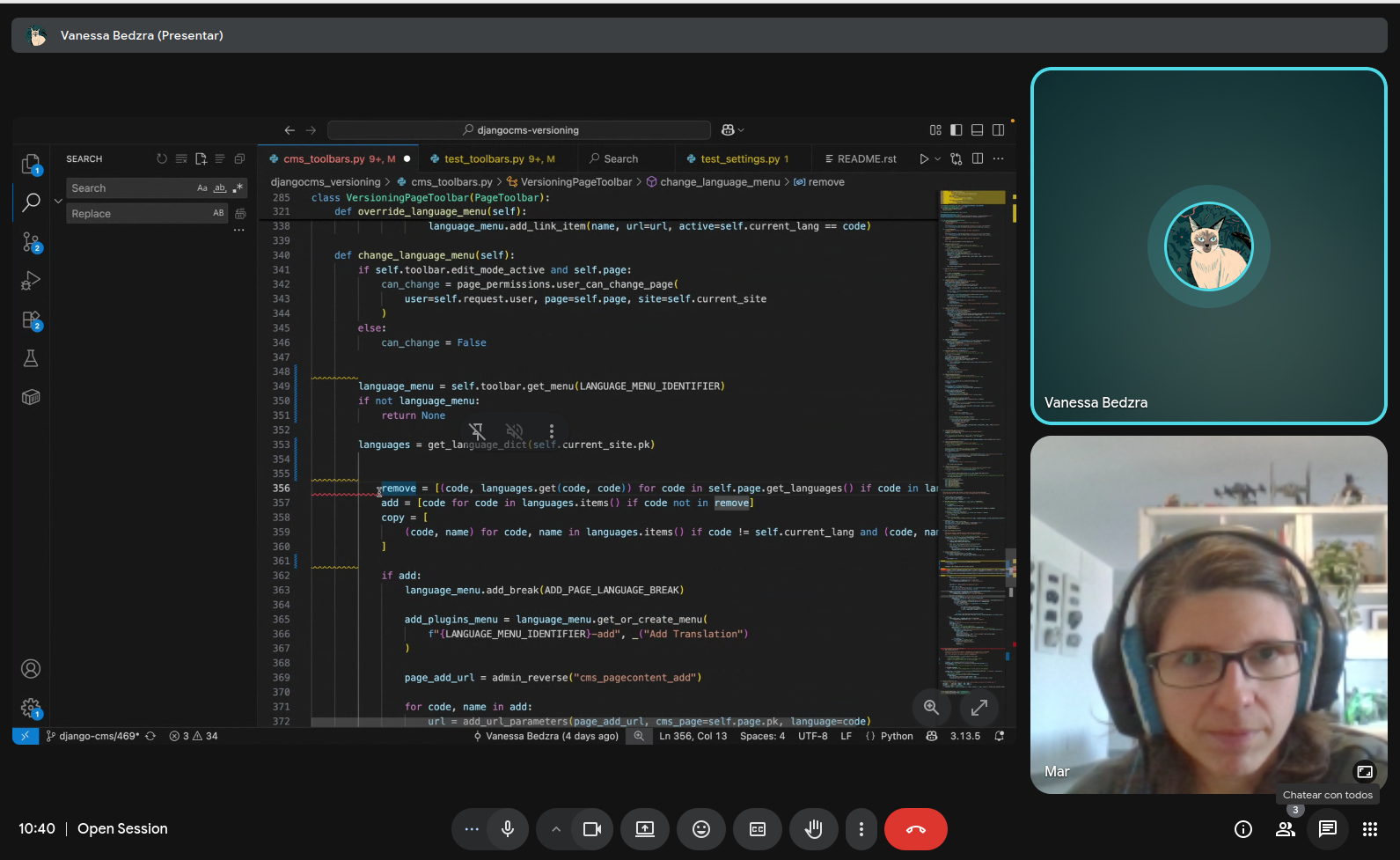

Djangonauts are encouraged to “chip in” into their peer’s doings, not just to help, but also to learn further. Peeking into you peer’s tickets and pull requests is a great way to learn, but also gives you the necessary context to help them if they get stuck - via chat discussions or even live pair programming sessions.

There’s nothing stopping you from adding comments into other people’s pull requests in fact, to provide further help or feedback. Or even having multiple people collaborating by pushing code into the same branch (with prior coordination, to avoid conflicts!).

To infinity and beyond

We’re still halfway through the program, but already I feel like it’s been a rewarding experience. It taught me valuable etiquette and best practices that will guide my future open source efforts, and most importantly, it helped me break that first barrier of making my first successful code contribution to an open source project, which has given me the necessary confidence to keep going at it.

I’m really grateful to the Django community for their welcomeness and dedication - it comes to show that when you cultivate a great community, you grow a great project!

This is just the first mission, but I’m sure more adventures in Django an open source will follow! 🚀